And now I'm seeing it everywhere.

|

| AFP/Getty Images |

What's the connection, other than those words? These women are all survivors, first of all. They went through something pretty horrible, and made it out alive. So let's just sit back and admire the hell out of them for a little bit.

OK. Secondly, they are all women who were made to serve. Reshma, and thousands and thousands of women like her, have been virtual slaves of the overseas garment-factory business. Only with the recent spate of high-profile disasters have we begun to notice, or care, what has been going on over there. We love our cheap fashion, and we don't care to think about how it gets on our bodies.

"I began working in Bangladesh's garment industry at the age of 12, making just $3 a month," said one former child laborer. "I went to work because my father had a stroke and the family needed money to cover basic living expenses. I worked 23 days in a row, sleeping on the shop floor, taking showers in the factory restroom, drinking unsafe water and being slapped by the supervisor."

In this industry, the women (and it's mostly women) are not only working for brutally low wages, they are often victims of other kinds of abuse. They have family depending on them for their survival, and their supervisors know it. There's no accountability, so the men on top of them get to do whatever they want: they can slap them, make them work impossibly long hours, send them into dangerous machinery, and force them to stay inside a building that is already collapsing, or in flames. Reshma was literally trapped inside, but her story is a poignant reminder of all the women who are virtually trapped inside those factories, and who never make the news.

Back to the Cleveland case: What's really insane about that story, to me, is how not-unusual it is. There have been far too many cases just like this one: Elizabeth Smart. Jaycee Dugard. Natascha Kampusch. Elisabeth Fritzl. All women—or girls, originally—held long-term as sexual prisoners. (There have been some boys held prisoner, too: just not as many.)

But this appalling story is even more common than these high-profile cases. We just notice those more because they're happening in our backyards, to people who look like us. In much of the world (not to mention for the bulk of human history), women are treated like the Cleveland three — and it is no big deal. In swaths of Asia and Africa, you will find one man holding several girls as sexual prisoners, and it doesn't even occur to neighbors to help them escape. They are called his wives.

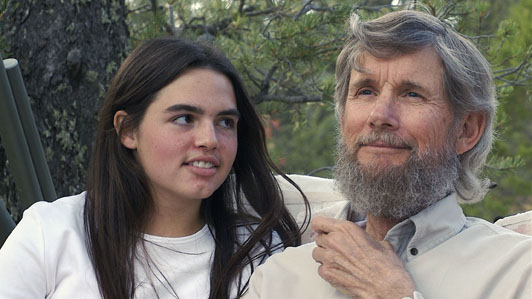

|

| Wayne Bent, of the Lord Our Righteousness Church |

I have my theories about what holds all these stories together, and what commonalities lie behind sexual (and economic) imprisonment of women, but I've alluded to them enough here. What are your theories? What leads to this kind of behavior, why is it so common, and how do we stop it?

|

Powerful question. I see it as not strictly sexual, economic, political, religious or social subjugation but as a combined evil that takes all these forms. When human rights are suspended by coercion, indoctrination, force, the best response comes from individuals who risk everything to insist upon fairness and government by discussion. This is the basis of labor unions, all equality movements and pursuit of individual dignity. Solution begins with educating people to their truer worth.

ReplyDeleteOh, I love this reply. And you're right: it is mighty dangerous to begin that education. Think of the price people like Malala (and her dad) pay, just for doing what we take completely for granted — but in a part of the world where it's heresy. Now *that* is courage.

DeleteJeez, you insist on making me think, dontcha? This is one of those issues I find particularly disturbing, because I can't think of any realistic solutions to it. How nice it would be if we could eliminate evil by simply insisting it shouldn't BE. And how wonderful if we could simply tell the oppressed to stand up for themselves and claim their rightful place in the world. True strength comes from within, but when a person's spirit has been broken and her options limited, that inner strength often dies a painful death.

ReplyDeleteSo true, Susan! It's interesting how some people have a crazy amount of resilience. I think that's part of what makes the stories of Reshma and the Cleveland women so awe-inspiring: their dogged tenacity, their will to live. But we can't really depend on that; we have to do something to help all those people who are or will be broken, who can't fight back.

DeleteI suspect that the economic imprisonment of women is an offshoot of the tendency of women to be sexually imprisoned in some form in most cultures through out much of human history. The situation for women in much of the developing world is not much different than it was for women in what are now the advanced industrial democracies in the too recent past. Women tend to be treated as sexual prizes whose job is to produce a great brood and please their spouses. I have a suspicion that this was not the case, or not often the case, and certainly not as extreme a case in our hunter-gatherer history.

ReplyDeleteIn any event when women can be traded by families, and married off without their consent it stands to reason that they will probably possess little political power, and enjoy vastly fewer protections under the law. In such situations dangerous exploitation cannot be far behind.

Is this connected to the kinds of situations we find in Cleveland where women are taken and held against their will for long periods of time? In some ways it has to be, but I think there is also the simple, and powerful desire for sex at work.

When people want to have sex with someone they tend to be natural coercers anyway, doing anything they can think of to coax their partners into the bedroom (or wherever). People will be seductive, people will beg, guilt trip, sometimes actually pay for sex and engage in all manner of persuasive technique to have sex. Enter violence and the threat thereof. Violence is a tool to achieve an end. Men tend to use this tool more than women, and so I think that is ultimately why we see men use violence to gain sexual access to their victims much more than we see women utilize physical violence to gain sexual access to a desired sexual partner.

Spot-on, Max. And this bit — "I have a suspicion that this was not the case... in our hunter-gatherer history..." — reminds me of something I read in a history book once: that the understanding of how sex worked, combined with the notion of private property, is what led to women's status taking a nosedive. Before that, people were more-or-less-equal, if differently employed in the tribe. After paternity and inheritance happened, it was all downhill for women. Not that I'd want to go back to the paleo-world (nasty, brutish, and short), but that seems a fair point.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete